How Does One Even Program a Robot?

A robot is characterized primarily by its versatility. It is a tool that can be used for different tasks in many contexts that each have their own special challenges. This makes it inherently hard to program a robot. Especially, if the resulting robotic system is expected to act autonomously and robustly in unforeseen situations.

Industrial automation is a well-established application field for robotic manipulators. Here, the act of programming usually means defining a fixed sequence of motions that the robotic arm then executes time and time again. When we instead think of a robot acting in a less structured environment like a home, the robot can not blindly follow a predefined sequence of actions. Because following this sequence will fail as soon as anything in that home changes. And as everyone living with children knows, changes must always be expected but can never be predicted.

Here, I am trying to develop an understanding of what it means to program a robot to act autonomously. And I hope that with that understanding it will be easier to see what may be missing in order to build genuinely autonomous machines. Like with many questions, AI is something that comes to mind as an answer. But at least for now, I am assuming a human to be involved in building and programming this robot. Nevertheless, fixing the problems I want to grasp here, will also help AI-based approaches.

I am trying hard to make this article approachable for both people who lack a technical background of robotics as well as engineers for whom some of the other concepts may feel a bit out there. I would be curious to learn if this worked. So please get in touch and tell me your thoughts on this topic.

On mystical creatures and system complexity

One blog post that brought this topic to many roboticist's attention is Benjie Holson's article introducing the important and mythical non-roboticist1. This is the person that simple methods to program robots are seemingly designed for, while the underlying problem is hard. But his point is that this simplification removes aspects from the programming that would have been needed to make the robot work. And in particular the article highlights two categories:

-

Environment Complexity: This is what I introduced on top with the messy home. You don't know in which exact environment the robot will operate, when you build it.

-

Stupid Bullshit Complexity: I think this can be called integration. Robotic control systems require internal components that are hard to use because they require very specialized configurations and data formats.

But the crucial point with both of these is that it is important to have a clear user in mind. And if I were to summarize the articles message, I think it is to respect the users intelligence and sanity by designing a way to program a robot that reflects the true complexity of the task to the user (intelligence) without introducing unnecessary complexities that they have to manage (sanity)1.

A concept that is worth exploring further is complexity. This term is used very broadly. Especially for computer scientists it has to be said that we are not talking about computational complexity. Instead, I want to start with an example from complex systems theory:

[...] a system that is complex, in the sense that a great many independent agents are interacting with each other in a great many ways. Think of the quadrillions of chemically reacting proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids that make up a living cell, or the billions of interconnected neurons that make up the brain, or the millions of mutually interdependent individuals who make up a human society.2

Note how the authors always compare individual entities like humans to their whole, e.g. the society. So, complexity must be understood as a difference between scales. This difference becomes apparent when one thinks about the implications of a statement like "To build a house, you don't need to know quantum physics". Here the complexity in the underlying quantum physics of all that belongs to the house is undoubtedly higher than that of the architectural plans including their execution. And it is the achievement of the disciplines of civil engineering to enable this without having to worry about quantum physics. This hints at one of my favorite topics, that is emergence. But for now, it is enough to understand that complexity is relative. And crucially, inside of a system it is smaller than outside:

The system does not have the capacity to connect a state of its own to everything that happens in the environment and to juxtapose one of its own operations to every environmental occurrence, in order either to enhance or to curtail what is happening. Instead, the system has to bundle and even ignore occurrences, and it must deploy indifference or create special arrangements for the management of complexity.3

For a definition of system, it should be sufficient in this context to think of a finite collection of items including some relations between them. This is somewhat aligned with a common-sense definition of technical systems. Crucially, all systems have an environment, which is simply everything that is not part of the system. But what does this mean for programming robots?

Building an Understanding of Programming a Robot

For a start we can think of robot programming in terms of dimensionality reduction. A humanoid robot for example has 30 or more actuators and every possible configuration of these can be thought of as a point in a 30-dimensional space. If I now want to tell the robot to move to a location on the two-dimensional floor of my house or pick up an object in the three-dimensional space, this is clearly a reduction.

But it is of course more than that. Because the robot can not magically take up any of these configurations, we must not only consider points but linked points, or paths, because only these are possible movements. The way of programming the robot must also adhere to these constraints. Additionally, programming will add the aspect of time. It will command the robot to be in a given configuration at a given time. A sequence of timed configurations is what we call a trajectory.

This is pretty much how an industrial robotic arm is programmed. Imagine a 30-dimensional hypercube, then draw a line through it. That is robot programming. Easy, right?

There are additional aspects, like labeling given configurations to make them recognizable, logic relations to other hardware, planning of trajectories between these configurations, like moveit does it in ROS. Additionally, this programming also considers basic limitations of the hardware. For example restricting the angles of joints in order not to damage the robot itself.

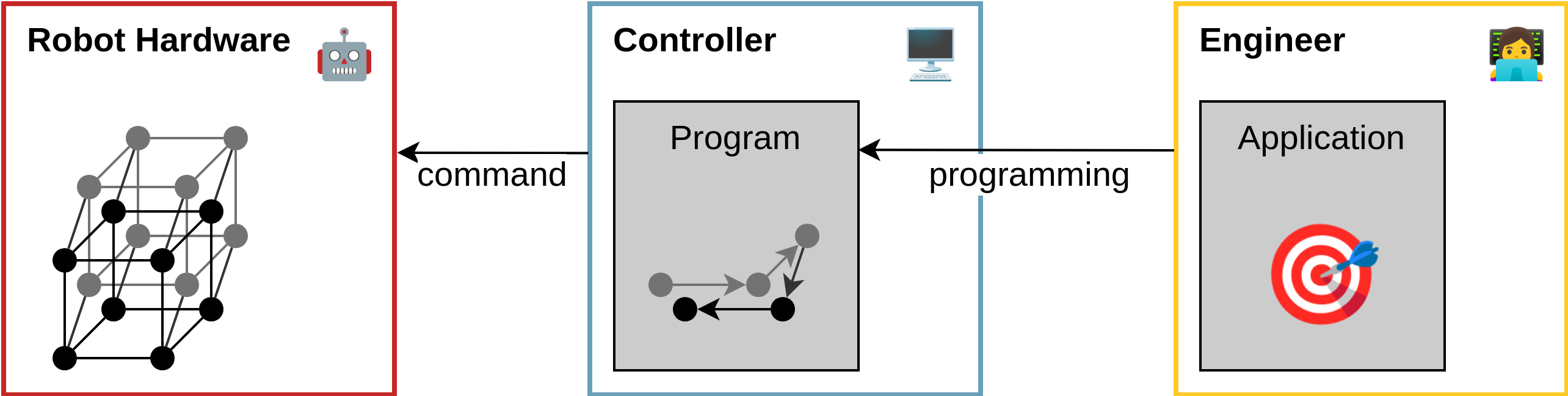

It is clear how this programming reduces complexity. The relative complexity in the system of the controller is lower compared to the actual robotic hardware and what it could do. This way to program a control system is effective at enabling developers to make the robot repeat predefined motions. What other systems could we think of, though?

About Systems and Languages

For example a language is a system. A system containing all words or symbols that can be used including some relation between them, usually referred to as syntax. Semantics is what we would consider the relation of the language system to some parts of its environment.

Also in that environment are all the words of other languages. If we think about programming languages, there may be changes when new language versions are announced. This then changes the language system by considering things that previously were part of the environment to belong to it. Human languages can also add to their system, for example when a new word is taken up by the society of its speakers. New words are often variants of words already present in other languages. For the general way how systems create themselves with respect to their environment, the Chilean biologists Maturana and Valera coined the beautiful term autopoiesis4.

Generally, I find it helpful for engineers that are constantly thinking about systems of some sort to have a clearer understanding of what this means. And luckily this is not hard at all. Firstly, it is crucial that every way to consider a system is just one arbitrary way to look at the world. For example going back to robotics, it is in no way set in stone what we should consider the system and what the environment. Simply, because there are many, in fact infinite possible choices. The most natural one is to look for example at a mobile robot and consider all the physical hardware that moves with it to be the robotic system. And, by difference this then also defines all the rest as its environment. That includes the surface it moves on, obstacles it may encounter, the outside world, and including even you, the programmer sitting next to it with your laptop. But I always thought that the most useful system border to draw may be that around the computer device controlling the robot. Because then, sensors and actuators are part of the environment and this mental model makes it way easier to consider inaccuracies in perception and the necessity to recover from wrong movements.

But let's continue to look at language systems: An interesting post that looks at robot programming from a standpoint of theoretical computer science is written by Dirk Riehle5. The article points out the need for a differentiation between the definition of a language and its implementation, when designing a way to program a robot. And programming languages must have clearly defined semantics5.

For example the now popular Behavior Trees are missing such a semantic, which is why we proposed one6. This general field of formalisms that allow to define the autonomous behavior of a robot can be called Robotic Deliberation. And I started my talk at ROSCon 2023 with comparing its relevance with that of the invention of programming languages by Grace Hopper7. While this may be thought provoking, it is also rather handwavy. In this article I will try to make it more concrete.

Autonomy with Skills

The approach in industrial robotics that is outlined above is effective at enabling developers to make the robot repeat predefined motions. Some more challenging things are possible, like reacting to sensor input to avoid obstacles in the way of the robot or changing the actual goal of the motion based on the perceived location of an object. But these approaches will fail for any scenario that provides less structure like outdoor environments or my house if I am honest. These scenarios require autonomy.

I would define a system as autonomous if it can make decisions towards a goal even if these decisions were not explicitly anticipated in the programming. Developing a robot to react to some conditions at runtime would definitely be feasible with what is described above. But crucially, it would be a very complex solution. These solutions must contain some mapping between a recognized situation and what the robot should do in this case. Think of a long list of conditions and actions.

How can we make this list shorter? By reducing the complexity further. To make it simpler to program the robot, we need to reduce the necessary complexity in the system or language used. For example with a humanoid robot, our language should definitely not have to think about the robot falling over, damaging others or itself. A programmer asking the robot to fetch an apple shouldn't have to worry about it falling down the stairs.

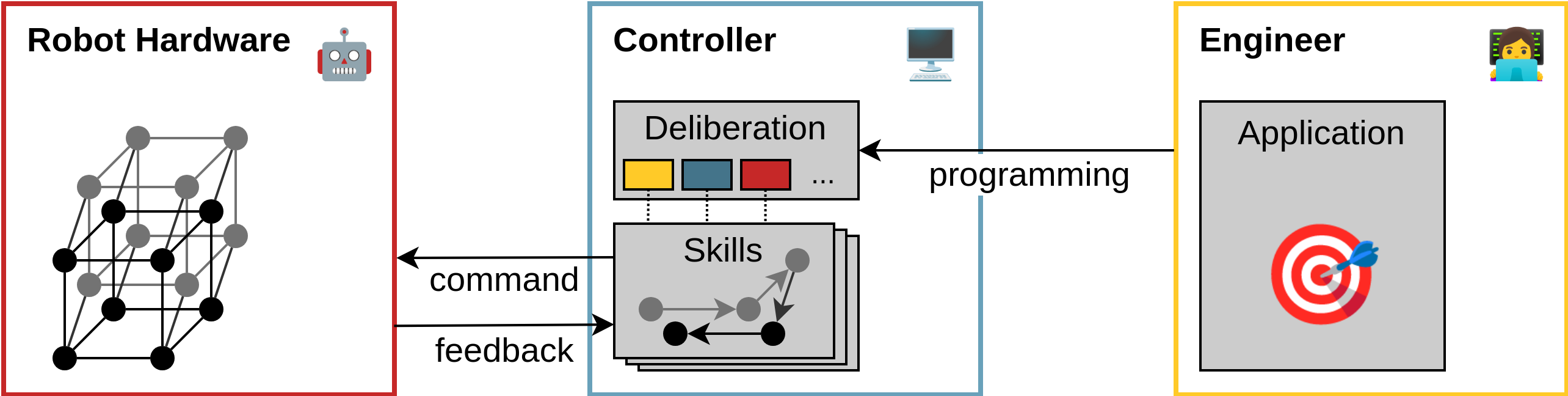

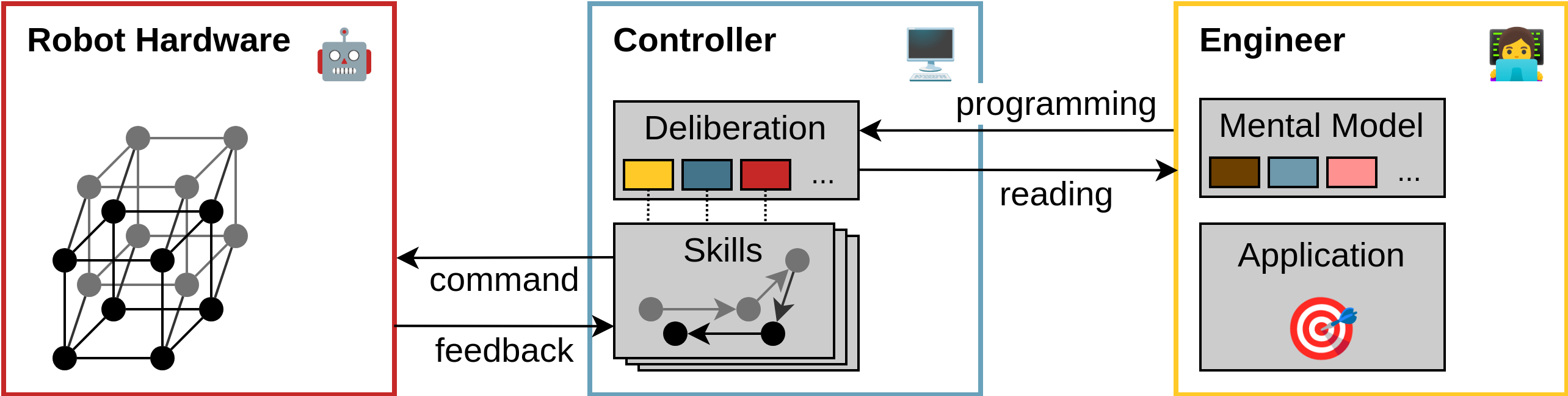

This is generally achieved by skill-based architectures. The controller must have blocks that are called skills which solve some functionalities without explicitly programming them. For example one skill will handle the complete movement of the robot. Then the act of programming only entails sending for example the goal location the robot should move to. The component that uses or orchestrates these skills towards a desired goal, is the deliberation layer, we talked about above. These or similar architectures could be considered state-of-the-art in more complex robotic systems8.

If we compare this to the mythical non-roboticist article1 and the two complexities, environment complexity and stupid bullshit complexity. Skills work towards addressing environment complexity, for example by handling the navigation to a given goal. The reduction of stupid bullshit complexity can be even seen as the primary motivation to introduce skill-based architectures. So, assuming a perfectly designed skill-based architecture, this type of complexity should be reduced to zero in the deliberation layer.

But, caution is necessary on the type of this complexity reduction. A design goal for a skill-based architecture must definitely be elimination of unnecessary complexity. And herein lies the challenge. How on earth should we know what may be necessary in this deliberation layer? We expect it to be useful for any possible type of application and it should even handle conditions that a programmer can not anticipate when programming. I guess we have to start somewhere. And I think we should start at the beginning of everything: the almighty creator - the engineer.

Programming. But in Your Mind

If we want to make sure that someone can program a robot as easily as possible, we have to elaborate which factors influence the ease of programming.

An article that is less specific to robotics but also looking into how humans interact with code is by Erik Bernhardsson9. It explicitly introduces the concept of a mental model that another human reading your code has. And this applies well to our question. The article then provides valuable and concrete tips in how to design the code that another developer interacts with. For example the valid suggestion to avoid the need for a mandatory configuration. Another one is to avoid conceptual overload, something that many robotics projects including our own work on formal verification can learn a lot from9.

But maybe we can look deeper into the idea of that mental model: Just like engineers, another group of people generally considered to be smart are chess players. There exists a very interesting body of research evaluating what it is about the minds of professional chess players that determines their success at chess. One may assume that people who are good at chess can simply think more logically or have access to better rationality in their mind, but the situation is different:

By confronting chess players of varying strength--from master to novice-with a perception task and a memory task, we have shown that the amount of information extracted from a briefly exposed position varies with playing strength. [...] The data suggest that the superior performance of stronger players (which does not appear in random positions) derives from the ability of those players to encode the position into larger perceptual chunks, each consisting of a familiar sub-configuration of pieces. Pieces within a single chunk are bound by relations of mutual defense, proximity, attack over small distances, and common color and type.10

Their results suggest that the success of a chess player is related to the size of the chunks they use to store chess boards in their memory. And the ability to retain these chess board configurations in memory is only present for configurations from actual games, not when the pieces are placed on the board randomly. This mental model emerges through repeated exposure to real configurations - not random setups, because these players built the models by actually playing chess. And their success is now not simply determined by how many hours they played but whether they managed to produce a highly effective mental model to quickly recognize and evaluate future board configurations.

To quote one of my favorite books of all time:

Learning high-level chess can be compared to learning to read. A first grader works hard at recognizing individual letters and assembling them into syllables and words, but a good adult reader perceives entire clauses. An expert reader has also acquired the ability to assemble familiar elements in a new pattern and can quickly “recognize” and correctly pronounce a word that she has never seen before. In chess, recurrent patterns of interacting pieces play the role of letters, and a chess position is a long word or a sentence.11

But what does this have to do with programming robots? I think, the success of building complex autonomous robots is also determined by the utility of the programmers mental model. If we want to make the programming of robots simple, we can not have the programmer invest hours and hours learning to read pieces of robotics applications. Instead, we must make sure that the language that defines the robotic deliberation logic supports the formation of a good mental model. Everyone learning a foreign language knows that this is no easy task, but that there are definitely easier and harder languages one could choose from.

What is missing?

I am unfortunately not in the position to propose a language that can deliver these things. And a blog post is also not necessarily the place to do so. All I want to do is to propose this as a perspective on the topic. And with that I can summarize what I think is needed in the field of robotic deliberation:

We need a language for humans. - For humans to program robots.

It’s tempting to think that LLMs will soon eliminate the need for programming. But LLMs, too, operate at a language level. And if we haven’t yet designed the right language for robotic behavior — one that reduces complexity in exactly the right way — then how could we expect them to work reliably?

The language we need must support three key qualities:

- Expressivity: Engineers must be able to express what the robot should do in a way that directly aligns with their mental model. This is about clarity and speed - the ability to quickly express ideas instead of getting your head around some formalism first.

- Interpretability: A second engineer or your future self must be able to read and comprehend the program quickly. This means that symbols must be unambiguous and structures must be easily graspable.

- Predictability: Given a program, the current state of the robot and its environment, it must be obvious and quick to predict correctly what the robot will do. This increases trust in the system and ultimately enables agency of humans interacting with the robot.

Without these properties, we can only build fragile, opaque, and unmaintainable systems - and then these systems will never be accepted.

The language doesn’t have to be textual or graphical. But it must support thinking. That’s the bridge between automation and autonomy. Between a program and a behavior. Between systems.

Feedback

I am very interested in your feedback. Feel free to reach out to me directly or consider sharing it here:

-

Holson, Benjie. 2024. “The Mythical Non-Roboticist.” Substack Newsletter. General Robots. https://generalrobots.substack.com/p/the-mythical-non-roboticist. ↩↩↩

-

Waldrop, Mitchell M. 1993. Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos. Simon and Schuster. ↩

-

Luhmann, Niklas. 2013. Introduction to Systems Theory. Cambridge, UK ; Malden, MA : Polity. http://archive.org/details/introductiontosy0000luhm. ↩

-

Maturana, Humberto R. 1980. Autopoiesis and Cognition : The Realization of the Living. Dordrecht, Holland ; Boston : D. Reidel Pub. Co. http://archive.org/details/autopoiesiscogni0042matu. ↩

-

“Visual Spaghetti Robotics Edition.” 2023. Dirk Riehle’s Industry and Research Publications. https://dirkriehle.com/2023/06/03/visual-spaghetti-robotics-edition/. ↩↩

-

Ghiorzi, Enrico, Christian Henkel, Matteo Palmas, Michaela Klauck, and Armando Tacchella. 2025. “Execution Semantics of Behavior Trees in Robotic Applications.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2408.00090. ↩

-

Christian Henkel. 2023. “Supporting Robotic Deliberation: The Deliberation Working Group and Tools for Behavior Trees (ROSCon 2023).” New Orleans. https://vimeo.com/879001877. ↩

-

Rovida, Francesco, Matthew Crosby, Dirk Holz, Athanasios S. Polydoros, Bjarne Großmann, Ronald P. A. Petrick, and Volker Krüger. 2017. “SkiROS—A Skill-Based Robot Control Platform on Top of ROS.” In Robot Operating System (ROS): The Complete Reference (Volume 2), edited by Anis Koubaa, 121–60. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54927-9\4. ↩

-

Bernhardsson, Erik. 2024. “It’s Hard to Write Code for Computers, but It’s Even Harder to Write Code for Humans.” Erik Bernhardsson. https://erikbern.com/2024/09/27/its-hard-to-write-code-for-humans.html. ↩↩

-

Chase, William G., and Herbert A. Simon. 1973. “Perception in Chess.” Cognitive Psychology 4 (1): 55–81. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0010028573900042. ↩

-

Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/56314/thinking-fast-and-slow-by-kahneman-daniel/9780141033570. ↩